A Collection of Short Reviews

The longest running series on Fox Hunting is “On Our Nightstand.” Though our overarching mission for the blog is to spotlight indie books and comics with a literary bend, this series focuses on whatever our contributors are reading and enjoying each week, regardless of the genre or form. This has allowed us to feature a wider variety of titles. And, since the reviews are short, they're great for quick referencing if at a book store. :)

The most recent incarnation of the blog features a handful of stellar posts in this series, and we continue to feature new books and comics every week. However, many great reviews from the past (officially a broken record here) are no longer available online due to the website change over to Tumblr.

I read a lot of really outstanding books last year, so I'm sharing every Nightstand post I wrote below.

December 1, 2014:

On break at work one day I stumbled upon Thomas Page McBee’s column “Self-Made Man” on The Rumpus. As someone already drawn to lyrically crafted memoir, I was hooked immediately.

Man Alive (City Lights Books) delves deeper into the two events that spurred a long brewing but radical shift in McBee’s identity. He traces the aftermath of his father’s abuses as he’s made to detail the events to his mother and a police officer at age 10. At 29, he and his girlfriend are mugged at gunpoint on a dark street in San Francisco. The mugger shows McBee mercy when he hears his voice and codes him as female. These two events and those built around them in their wake expand and undulate in Man Alive, through vivid language and a deft examination of how they shape the person he’s become – and who he’s always been.

McBee meditatively repeats the acidic intonation women attach to the word “men,” like when his mother discovered what his father did to him: “Men, she’d said then. And I’d learned to say it in the same way, a lemon in my mouth.”

What makes a man emerges as a nebulous and entirely individual-based concept. And McBee unflinchingly runs toward his own evolving meaning of manhood, facing the ghosts of his past. Though often painful, his journey is mapped and detailed with great beauty. I’m a third of the way in and it’s difficult not to zip through each short chapter. But I’m trying to walk my way through this one, at a pace fit to take everything in one step at a time.

November 17, 2014:

Lacy M. Johnson’s The Other Side (Tin House Books) pieces together the sharp-edged memories of a past abusive relationship that left an indelible imprint on her. It begins with her escape after her ex-boyfriend (referred to only as "The Man I Live With") kidnapped, imprisoned, and raped her. Johnson’s memoir grabs you, shakes you so hard you’re too stunned to immediately process it, and never lets up.

Woven into fraught scenes with her former boyfriend and Spanish teacher are painfully relatable insights:

“That image, of the self, does not belong equally to everyone. As a woman, I must keep myself under constant surveillance: how do I look as I rise from the bed, and while I walk through the store buying groceries, and while I run with the dog in the park? From childhood I was taught to survey and police and maintain my image continually, and in this role—as both surveyor and the image that is surveyed—I learned to see myself as others see me: as an object to be viewed and evaluated, a sight.”

Johnson’s writing is a force to be reckoned with, as is her spirit. I’m halfway through the book at the moment, and it’s as difficult to fully allow myself to feel the words as it is to tear my eyes away from them. I will definitely seek out and read anything she writes in the future.

November 3, 2014:

As a long time fan of short fiction, I’ve been hearing Amy Hempel’s name since high school. I picked up Reasons to Live in undergrad, lifting it off the shelf of a college bookstore and feeling like I was about to dive into something that would change my entire view on the form. I flipped through the stories, confused that some were only a couple of pages long. I took a step back from the book. I didn’t get it. I wasn’t pulled in by these sentences, which were alien in their self-assured brevity.

But I kept creeping back to Amy Hempel over the years. Kept picking up another slim volume and stealing a glance inside. Was I ready now? Did it make sense?

At the library branch I have come to think of as the “one with all the best short story collections” this weekend, I did a quick search for Amy Hempel. I had a feeling. The book waiting for me was heavy rather than slight. I placed The Collected Stories of Amy Hempel (Scribner) into my backpack. I knew it was time.

How could my readerly brain have needed this long to see the magic in these sentences? The depth and mystery contained in the very first story, “In a Tub,” which is a mere one and a half pages – blew my mind. When I was younger, I felt a deep need for a plot as bold and taut as a tightrope, and these flashes into characters’ psyches felt like looking at a puzzle with missing pieces – a little bundle of mental work I felt like I shouldn’t have to parse. I wanted the work to do the work for me. Now, the stories I’m reading feel radical and thrillingly familiar. A handful of thin pages contain quick glimpses into lives as deep and unknowable as wells, mingling the mundane with small moments of magic. It feels like I'm learning about myself, reading this now.

Some books are worth the wait.

October 27, 2014:

Margaret Atwood has been a favorite of mine for years. Reading Oryx and Crake was basically a revelation. So when I heard she was releasing a new collection of short stories this fall, I had to have it immediately.

Stone Mattress (Nan A. Talese) begins with a set of linked stories, each spotlighting key members of a community of writers in the twilight years of their lives. In “Alphinland”, Constance faces an ice storm after the death of her husband. As the wildly successful creator of the fantasy novel series, Alphinland, she has built a world inhabited by analogs of her former flames and foes alike. Her ex-boyfriend, Gavin, resides in a state of suspended animation, hidden in an oak cask in a deserted winery, while Jorrie, the woman he cheated on Constance with, is stung by hundreds of emerald and indigo bees at exactly noon everyday. Gavin and Jorrie don’t fare as well later on in life (though by no means as dramatically as they do in Alphinland), as seen in their own stories, “Revenant” and “Dark Lady.”

Atwood’s characters, as always, are fully realized and endlessly fascinating – even when only given brief time to shine in short stories. Her take on epic fantasy novel series (including the disdain her old poet cohorts consider them with) is both familiar and refreshing. I’d read a book set in Atwood’s Alphinland, that’s for sure. I’ve only read three stories so far, and though I’m sad to leave this group of friends behind, I’m thrilled to see who (and what) Atwood introduces me to next.

October 21, 2014:

I picked up Merritt Tierce’s Love Me Back (Doubleday) after I heard her on an Otherppl podcast and was thunderstruck by her raw honesty and passion. When I got my hands on her debut novel, I wasn’t surprised at the fierce immediacy I felt with protagonist Marie, who still lingers with me long after the final page of the story.

Marie becomes a mother accidentally at a very young age. Her response to this unforeseen shift is complicated, seeming at first to be outright rejection. A career server, she moves from restaurant to restaurant, carving out a reputation with each crew. Marie doesn’t shy from her proclivity for substances or sex. Though this proclivity is in part a reaction to grappling with her feelings regarding her daughter, there’s no sentimentality to be found. When reminded of her reputation by coworkers, she doesn’t even blink. She acknowledges all of her actions, brutal as they may be to witness, as her own choices. There’s no linear narrative or plot here, only flashes in a timeline, from before Marie became pregnant to her later days working at a high-end Dallas steakhouse.

A searing character study, Love Me Back, brings you unflinchingly close to Marie’s interior life. It draws a perfect circle around an unforgettably human character often erased from both life and literature. Tierce now sits on my list of favorites, alongside my old standby, Mary Gaitskill, who I am reminded of throughout Love Me Back.

October 6, 2014:

Women in Clothes (Blue Rider Press) began as a conversation between friends and blossomed into a tome that offers a glimpse into the lives and minds of over 600 women and the feelings they attach to clothing. This collection, edited by Sheila Heti, Heidi Julavits, Leanne Shapton, and Mary Mann, finally gives the way we dress and present ourselves as women—often lumped into the category of frivolous lady interests—the examination it deserves. What stories lie in the well-worn lines of that denim jacket you admire on the woman in front of you at the grocery store? Have you ever thought of the memory cues a piece of an outfit might elicit in someone who labored hours on end as a child to construct it for the unknowing wearer (e.g. cummerbunds)? Women in Clothes lays out a chorus of diverse voices presented in survey and short essay form.

The book is described as a conversation amongst women, and it is fitting that I came upon it through a conversation with a female coworker of mine. I expected to be intrigued by the anecdotes and survey answers, hoping to gain a new sociological perspective. The book is definitely interesting in that way, but more so, it’s moving. One section pairs old photographs of writers’ mothers with blurbs that describe what the writer thinks about them at each moment pictured—what their clothes seem to say about them, who they once may have been. I found myself tearing up over the singular stories, but also at the sudden, intense feeling of connection with all of the women involved.

Readers and writers are often highly observant, but Women in Clothes adds a new layer (pun intended) to how you can see the world. And once you start reading, you’ll want to share it with others immediately, adding to the already vibrant conversations and connections that spring from this collection.

September 23, 2014:

In the world of Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven (Knopf), the Georgia Flu epidemic has swept across the globe, killing countless people and sending civilization back to a time before electricity, a dangerous time in which strangers cannot be trusted. The novel begins the night that the flu descends, with fake snow falling softly around a modern production of Shakespeare’s King Lear. As Arthur Leander, star of the show and once-famous actor, succumbs to a heart attack, a paramedic rushes the stage but it is to no avail. A young actress bears witness to the spectacle, her handler nowhere in sight, and cannot be calmed down. More than a decade later the flu has done its damage, and that same actress, Kirsten Raymonde, has joined a traveling symphony who perform Shakespeare for tiny towns as they travel by caravan. She can’t remember much of her life before the flu, but searches for clues about Arthur’s life, clinging to the science fiction comics he gave her shortly before his death, a couple of issues of Station Eleven. When Kirsten’s traveling symphony encounter a dangerous man who claims to be a prophet, it isn’t long before the members of their caravan begin to mysteriously vanish as if plucked from the sky.

Station Eleven slowly builds an ominous atmosphere around its characters, settling the reader into this new world that has no spotlights to illuminate stages, no hum of air conditioning to cool its inhabitants, and no solid sense of safety. Through a series of flashbacks to Arthur and other character’s former lives, old ghosts reach out their tendril-like hands to steer the future. I’m a little under halfway through and am enamored with the story, especially with the character of the artist who created the Station Eleven comics. I can’t wait to see where these characters end up and whether their paths will cross or diverge throughout the wild and new frontier.

September 17, 2014:

After a bit of a reading slump, I flagrantly ignored my TBR pile and impulse ordered the first book that really struck my interest. This turned out to be Excavation: A Memoir (Future Tense Books), by Wendy C. Ortiz. When it arrived in the mail I eagerly dove in, falling in love with the fluid prose and the immediacy I felt with teenaged Ortiz. When she was thirteen, a new, charming 28-year-old English teacher arrived at her middle school. A quick and passionate fan of her writing, this teacher soon initiated long telephone conversations with Ortiz to discuss the book she was working on. As she curled around her princess phone, he professed to having a crush on her, thus beginning a five year sexual relationship that would shape her and all of her future relationships to come.

Ortiz pulls you inside the skin of her teenaged self, never shying away from the pain and confusion she navigated. The home she shared in Los Angeles with her alcoholic mother feels palpably cavernous; her freedom is vast, but the responsibility of being the only capable family member is suffocating.

Rather than stepping out of the narrative to comment on the relationship, or detailing the later fate of her teacher (now a registered sex offender), Ortiz keeps the reader firmly held within her headspace as a teen. This makes each scene of manipulation and abuse all the more powerful; without a voice to supply safe distance and guidance through the darkness, you’re left only to feel it, attempt to analyze it, and work through it with her. The lines between you seem to blur.

The day I received the book I raced through half of it. I caught my dog chewing through the bottom corner of the pages that very night. Unable to wait for a new copy, I resigned myself to gently ripping each of the melded pages apart as I turned them. The tearing sound felt oddly fitting as I pulled apart the last bits of Excavation. I haven’t felt so many things while reading in ages.

September 2, 2014:

Amy Bloom’s name has been popping up all over the Internet lately. I know she’s recently released a new novel, but everyone praises her as a master, a title often reserved for authors who have established a more well-known body of work. I tend to gravitate toward short story collections when it comes to determining an unfamiliar writer’s true prowess. There’s just some glimmer of magic in short fiction that not every writer can capture. Turning to Where the God of Love Hangs Out (Random House), I quickly learned Bloom has that magic touch.

The first four stories in the collection are interconnected. Partway through, it seems like the whole book will be about Clare and William and their respective spouses, but Bloom weaves their beautiful, painfully familiar story in just under sixty pages. She dips in and out of the mundane lives of two long-term best friends turned lovers, exploring how slow burning love in one’s middle age can feel just as intense as it does for the young. It’s shocking how little melodrama features in this affair story with a melancholy ending, and equally surprising how little needed to happen for me to be sucked in immediately. No longer skeptical, I’m onto the next story and eager for more.

August 25, 2014:

This week my reading took place almost entirely on airplanes. Needing a book that would sustain my attention for hours on end, I turned to Annihilation (FSG Originals) by Jeff VanderMeer, the first in the Southern Reach trilogy. Before I even read the novel’s premise, I was fascinated by FSG Originals’ decision to release all three books sequentially this year, an odd choice for a publisher. The books are set in mysterious Area X, a remote bit of wilderness totally cut off from civilization. At the time that the novel takes place, there have been ten previous expeditions to Area X, from which most party members did not return. Those who did reappeared in their homes with no memory of how they got there, and all died of cancer not long after. Annihilation follows the eleventh expedition. Four women—known only by their roles in the group as the anthropologist, the surveyor, the psychologist, and the biologist—quickly discover that Area X holds more startling secrets than any of them could have imagined.

VanderMeer’s writing edges on the literary, elevating a plot that initially echoes the familiar atmosphere of television shows like Lost and The X-Files. Above all, it was the odd relationship between the biologist and Area X that gripped me the most. An intense lone wolf who places her work above all else, the biologist’s experience offers an unusual lens through which to view all the mysteries of the strange setting.

I’ve just picked up Authority, because once you’ve read Annihilation you can’t really stop there. I can’t wait to dive back into the eerie landscape of Area X.

August 11, 2014:

This week, after feeling its pull from the row of shelves currently slanting perilously off of my wall, I picked up a book I’ve had lying around for a while now: Jo Ann Beard’s collection of autobiographical essays entitled The Boys of My Youth (Back Bay Books). In these essays, Beard dives in and out of her memories, starting with her childhood in the ’60s. She wanders the home of her grandparents, rooms laden with what, to her, appeared to be nonsensical junk—jars full of buttons, ornate furniture, and one rotating fan that seemed to move of its own accord. One evening, sprawled on the floor as Bonanza plays above her on the glowing TV screen, she feels the weight of the stillness of her grandmother’s current existence. One long street with no curves or forks—just a series of quiet days toiling in that house crammed with so much life debris. She begins to sob, thinking: “I’m a monkey, strapped into a space capsule and flung far out into the galaxy, weightless, hurtling along upside down through the Milky Way. Alone, alone, and alone.” Her parents come to pick her up when she can't calm herself. When asked about it later she replies, “Bonanza made me sad.”

Later, Beard and her cousin careen through dusty dive bars and blast down country roads, narrowly avoiding true danger but always finding just the sort of trouble they’re after. She correlates their own thick bond with that of their mothers, who smoked endless cigarettes and drank as they ruminated about the girls they were about to usher into the world. Two “mouthy, spindly-legged girls” not too different from themselves.

Beard’s prose hums with electricity, and the players in her past, including her younger self, all shine with a melancholic beauty. I’m eager to see where life takes her next.

August 4, 2014:

After a long spell of reading books driven by dark themes, I picked up Kate Racculia's Bellweather Rhapsody (Houghton Mifflin). The Bellweather Hotel has shades of the modern day version of Wes Anderson's Grand Budapest Hotel with a tinge of sinister murder mystery mixed in for good measure. After witnessing a murder-suicide as a child bridesmaid in the Bellweather, Minnie has returned to confront the scene that haunts her still. At the same time, hundreds of gifted high school musicians flood the hotel for the annual Statewide competition, including twin prodigies, Rabbit and Alice Hatmaker. To top it all off, an impending snowstorm threatens to trap them all on the decrepit grounds of the Bellweather as tensions rise and mysterious happenings begin to occur.

A mammouth, past its time hotel housing a host of quirky characters will get me turning pages every time. Racculia, a former bassoonist herself, layers in vivid insights into the lives of young musicians. The characters all teeter on the edge from the get go, but Racculia infuses humor into the escalating plot, creating a tumbling joyride for the reader. Though there's a snowstorm, this is definitely my kind of summer read and I can't wait to continue.

July 28, 2014:

This week I was on the hunt for another engrossing memoir complete with lyrical language, vulnerability, and insight into issues I'm familiar with—a similar style to that of Cheryl Strayed's Wild. I picked up Justin Hocking's The Great Floodgates of the Wonderworld: A Memoir after spotting the Graywolf Press logo on the spine. You know how some books just seem to find you at the perfect time? That's how this one felt.

Hocking uproots himself from a comfortable life in his home state of Colorado to follow the dream of being a writer in New York City. With an obsessive passion for skateboarding and emotionally tumultuous relationships, he finds himself far from the anchor of his girlfriend and soon tethered to a soul-sucking job in "the pit" of a major publishing house. He carries with him an obsession with Herman Melville's Moby Dick, and he soon finds parallels to it in the new hobby that helps save him from an otherwise rocky era of his interior life: surfing at Rockaway Beach. Hocking intersperses the history of surfing and of Melville and his masterpiece with memories that jump through time, retracing the destructive patterns he attempts to free himself from. His journey is both painful and poignant. It will resonate with anyone who has ever faced their demons head on and chosen to sit in their suffering rather than drown it out. Hocking finds solace in his shared connection to the sea with his hero, Melville:

"The ocean was for him--as it was for me during my New York years--the one place that felt like home, a lush wave garden free from all the thorns and thistles of the broken world."

One can't help but feel a similar connection to Hocking through his immersive and laid bare writing.

July 21, 2014:

I have really been meaning to read more poetry since - well, since I can remember. But, it turns out I'm not very adept at finding collections that speak to me. Enter: Lauren Ireland's collection of postcard poetry, Dear Lil Wayne (Magic Helicoptor Press). Ireland wrote short but poignant poem-letters to Weezy during and after his 2010 incarceration, compiled within this small, purple book.

Ireland ruminates on impending death, the feeling of being in love, what it feels like to be a poet, and an impossible to evade sadness. Hints of humor and references to hip hop weave amongst these musings: "...I tried to understand why I am always so sad. Too many bitches, not enough crew. I feel better when I tell you things. For a minute." The deftness of Ireland's words strikes a cord - her short letters may not hit their target audience (Weezy), but they sure hit home for readers. Though it's painfully lonely at times, it spurs an instantaneous sense of belonging at its high points: "You wouldn't understand, but it's hard to be boring in a fascinating world." I'll definitely be picking it up and rereading random poems - for both the humor and the pathos.

July 14, 2014:

My attention span and the rising temperature outside seem to be inversely proportional. Thus, I knew I needed a page-turner, but I wanted something character-driven that still had a literary writing style. This week I turned to Megan Abbott's latest novel, The Fever (Little, Brown and Company). In sleepy, small-town Dryden, the Nash family's lives center around high school. Though the perspectives rotate between Tom, the patriarch, and his teen children, Eli and Deenie, it's Deenie who sets the stage: her best friend has a seizure at school, sparking the spread of a mysterious contagion.

The premise may sound like a combination of a teen drama and a post-apocalyptic thriller, but The Fever breaks free from both molds. Though still glued to their cell phones and tethered to their precarious social statuses, the teens that inhabit Dryden never read as caricatures or mere plot devices. Abbott mirrors the fever-like state of adolescence with the hysteria induced by the contagion. Awash in murky atmosphere and pulsating with suspense, The Fever will make you forget the summer heat.

July 7, 2014:

After listening to Smith Henderson's interview on Brad Listi's podcast, Otherppl, I knew I had to get my hands on his debut novel, Fourth of July Creek (Ecco Press). I have a penchant for stories detailing the lives of social workers, and Fourth of July Creek ups the anty with protagonist Pete Snow mirroring his clients with a life equally out of control. An alcoholic disconnected from his own family, Pete crosses pathes with Benjamin Pearl, an eleven-year-old boy raised in the woods. He tries to help him, but quickly learns Benjamin has more up against him than tattered clothes and sore-ridden feet. Patriarch Jeremiah Pearl greets Pete in the woods with gunshots and whisks his son away, first forcing the boy to strip off his new civilian clothes in the frigid wilderness. Pete is left to grapple with the sharp edges of his own life as well as a brewing manhunt involving the F.B.I. and none other than Jeremiah Pearl himself.

I'm not very far yet, but I'm already swept away in the current of the lives of Pete and his charges: all dragged too far out to catch a glimpse of the safety of shore. Additionally, Henderson's language highlights the raw beauty of the Montana landscapes his characters tear through. I'm hooked.

June 30, 2014:

I’m always on the lookout for new short story collections to devour. Recently, one title kept popping up all over literary lists: Austin-based author Elizabeth McCracken’s Thunderstruck & Other Stories (The Dial Press). Almost immediately, the language leapt out at me. In the first story, “Something Amazing,” McCracken writes of a neighborhood west of Boston after the death of Missy Goodby, a six-year-old stolen by lymphoma. Missy’s mother retreats into herself as rumors swirl among the neighborhood children that she’s a witch. “The soul is liquid, and slow to evaporate. The body’s a bucket liable to slosh,” McCracken writes. Tragedy finds new ways to bloom as two brothers from the neighborhood lose their way, one crossing paths with Missy’s mother, which results in a tender, unsettling scene.

McCracken describes the delicate ways people find to twist the knife into their own hearts. However, she still leaves room for the brief moments of small whimsy that brighten everyday lives. Just reading the first few pages of her work reminded me of the magic feeling of discovering those truly electric, succinct turns of phrase found in the best short fiction.

February 3, 2014:

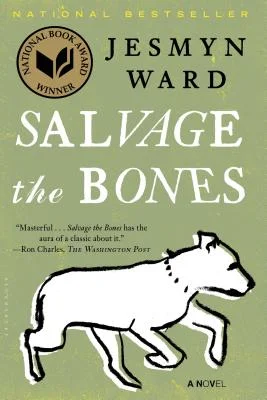

I just started reading the winner of the 2011 National Book Award, Salvage the Bones (Bloomsbury USA), by Jesmyn Ward. Fifteen-year-old Esch lives in Bois Sauvage, Mississippi, with her alcoholic father and three brothers. A hurricane brews over the Gulf of Mexico when the book opens, while Esch’s brother Skeetah’s pit bull is in the throes of labor.

The book spans 12 days, following the tribulations of the poverty-stricken family from Esch’s perspective. Though I’m not very far into the story, I’m already gripped by the lyrical writing. The description of China, Skeetah’s pit bull, in labor is vivid and balanced with both beauty and grotesqueness: “Everything about China tenses and there are a million marbles under her skin, and then she seems to be turning herself inside out…China is blooming.” Each character springs immediately to life. Esch's observations thrum with heat and a feeling of impending change. I’m eager to find out what unfolds as the family grapples with one another and the looming storm ahead.